Vibrational Match

Looks like the publisher of this story has gone fully offline, so I’ll post it here!

"What is that sound?" said Sutwin. "A Hobart CLeN?"

“Can I get a consensus check?” said Ally.

It was quiet in the room as we listened, but then, it was designed to be. Quilting bulged, voluptuous, from the weave of a Faraday cage, blocking electromagnetic interference and radio waves from adding their low buzz to the target sounds. Processors sat, stripped of any cooling fans or rotating heads, on dry ice blocks whose slowly-dissolving mist filled the room with its own atmosphere. Everyone's clothing was padded and de-textured, and a large "NO CORDUROY" sign hung at the entrance, late-arriving compensation for a past disaster. Left alone in this room for too long, you could lose your place in the world; you could emerge, hours later, eyes blank, lost forever.

But I was not alone here. I had my fellow researchers. We were gathered here listening very closely to room tone: the sound of a silent space, of the rumbling machinery and gurgling pipes and whirring fans that float, ghostly, in the background of any indoor space. I have learned that the process of filming a movie required actors to re-record dialogue in a soundproofed recording studio. But a vocal booth is as unnaturally silent as the shielded space in which we were doing our research—indeed, bands were sometimes known, I’d heard, to lose their minds in a recording studio—so the new recording has to be mixed with the sound of the room where the scene was filmed. To make that possible, "room tone" is recorded on a silent set before filming is wrapped. A false reference to the real space.

This is what they used to do, anyway, back when people were allowed to make movies. Or to record anything at all, not just speak them into another's ear, as I am doing to you here. The recording we were listening to, this room tone, had been miraculously salvaged from a student film shot in the Six Companies Center just three hours before the building collapsed. The disaster was assumed far and wide to be an act of terrorism, given the company's role in the then-ongoing data cataclysm. But it had never been conclusively explained. There was no precipitating mechanism.

The team I’d joined was investigating a theory that the collapse could be explained by an accidental confluence of vibrations: that some sympathetic resonance had nullified the building's baffler, that slab of concrete installed below the eaves of skyscrapers to absorb the energy from the high winds, which otherwise would cause the spire to sway to and fro. Strong winds to the south would buffet the tower, and the baffler slab would swing southward, offsetting the motion. If it didn't swing, then the tower would. It was possible, but extremely unlikely, that the rhythm of every rotating device in the building had lined up long enough to shake the baffler off its course; a miraculous confluence; a harmony of the spheres. So, by listening with minute care to the sound of a vacant office, we were isolating every vibration that could point us toward an explanation, marking the cycles and time stamps on a blueprint of the building. If enough of them aligned, that might explain the collapse. It was a little ridiculous, I agree. But now that we were forbidden from creating new data, researchers—those like me, Pavlovian dogs hitting a button long after food had stopped being dispensed—had to find compelling reasons to dig into the past.

“Let’s hear the reference tone,” Vashti said. Ally nodded and tapped on a touchscreen. A rumbling hum came through the speakers. It was the sound of an old commercial dishwasher, clipped from a YouTube product review.

“Do we have consensus?” Sutwin pushed.

"Aye," said Vashti.

"Aye," I said.

"Consensus achieved," Ally said. "Entering in the database. Validation, please."

I looked up on the big screen and saw that Ally had entered "Hobart CL64ENVY-1, 0.5 Hz" in a new row. "Validated," I said, and Ally tapped the screen again, locking the data in place. It was real now; it would live, in some form, forever.

The sound played on a loop. "Now let's talk about the distance," Sutwin said. "Pull up the map."

I know this song-and-dance all sounds strange to an elder like yourself, who's only recently emerged as part of the reclamation. But this is what I grew up with. Oldsters like Sutwin—those who hadn't generated enough personal data to be corrupted; who retained their original selves—put in place these data regulations, and a set of values to go along with them: data is precious, rarely created, and almost never stored, blah blah blah, I'd heard it literally a thousand times. But what does that mean, you might ask. Listen: If you search your memory, back from your adolescence, before the dark period, you might recall sending an application packet to art school that included your test scores and grades: blurry printouts of numbers on a misaligned grid. But when I applied to college, the committee didn't look at my records. They couldn't. They didn't exist. Instead, they called up my guidance counselor, who'd talked to all my teachers and told them that I was a good student, one who they should recognize when I walked onto campus in six months' time. The committee members then remembered my information using one of the common mnemonics, or, if they suffered from a disability, wrote it on a piece of paper that was later burned. When they accepted me, I was told by a phone call. My parents would have been proud; it was a good school. But mom and dad—this is what I'm trying to tell you, this is why I'm saying all this into your ear—didn't remember they were my parents anymore. They still don't.

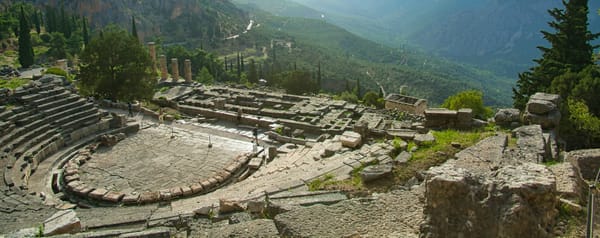

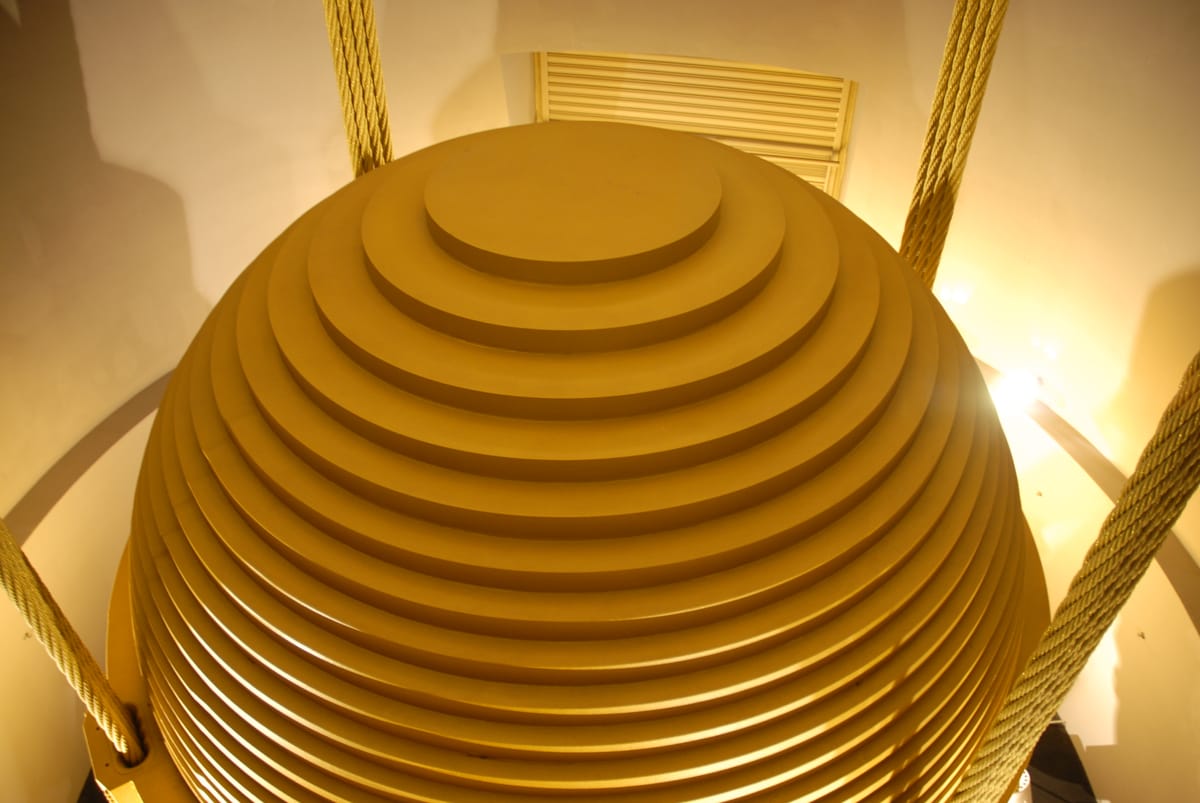

My parents were artists. I took an art history course in college, and one of my dad's works, a non-figurative sculpture called "Fundamental Frequency," was on the syllabus: a simple white plinth with a stack of eight rotating speakers on top, situated in a soundproof room with eight empty pedestals. Every fifteen minutes, the audience would come in, bringing objects to put on the pedestals: a bell-like wine glass (sing, yourself, to a some stemware, and you'll hear it resonate; try it now; do you remember?), or a rattly tin can, a selection of which were available in a bin in the waiting room. Hollow things; open things. Containers of air, waiting to be filled with sound. Once the door was closed, the speakers would slowly rotate as they emitted an A, a sound wave oscillating from peak to trough 440 times per second. The pitch would gradually increase, sliding up from an A to a B-flat, until a microphone in the plinth detected some unexpected vibration in the room; a nearby vase, say, rattling on its pedestal. When that object echoed back—when the diameter of the vase matched a multiple of the distance between sound waves, causing its porcelain to wobble—the bottom speaker would lock in place, pointing toward the object. It would continue playing the resonating tone while the remaining speakers moved on to higher notes, rotating until each had found a match. Then all eight sounds would play until the 15 minutes was up.

The resulting sound varied wildly depending on the objects placed in the room. Sometimes it would be discordant, producing an overall tone that beat against itself in an unsteady rhythm—wub,wub-wub-wuuuub-wuuuuuuuub—and sometimes not all eight speakers would find a match, causing the tone to soar into a whistle. But when conditions were just right, and the objects had fundamental frequencies in clean ratios, the sound would build on itself to reach a steady tone, at a volume that you could feel inside your mouth, the spit next to your back molars seeming to bubble up of its own accord. Viewers said it sounded like a trumpet, or angels shouting. (Do you remember that? Do you remember the sound? Did I describe it right? Here, let me brush those ashes from the curls of your hair. It's so gray, now.) It sounded to me like a laser beam. I could envision it shooting out from the top of the sculpture and reading some old CD spinning on the ceiling.

"Bah," said Anita, the back of her little hand brushing my soft cotton pants as she chased a plastic ball across the room. Anita was Vashti's conscience, there to fulfill a requirement that researchers have someone precious in the room with them, a family member or a very close friend, someone they wouldn't want witnessing their unethical behavior Ally and Sutwin had brought their spouses, who sat outside the quiet room, attending to their own business. Vashti had brought her daughter, a wobbly little linebacker who could reliably keep quiet when we were listening closely. But there were a lot of breaks like this, where Anita could just frolic. All the equipment in the room had been raised a few feet off the floor so she wouldn't disturb it. Anita would try to interact with it anyway, gripping a secured pole tightly and trying to rotate it—doing baby science experiments on the normal functioning of physical space—until Vashti ruffled her hair and distracted her with some toy. I was about Anita’s age when dad de-referenced, six months or so after mom did, one of the earliest cases. (Do you remember that? Do you?) I was so young, they figured it was second nature for me to be leery of data, so I wasn’t required to have anyone there. I was my own conscience.

On the big screen, Ally was slowly panning around an image of the office’s walls. A map on a second screen tracked the orientation of our virtual camera. These images were all boringly familiar to us, as we'd gone over them with a fine-toothed comb and highlighted any physical objects that could create vibrations. There were a surprising number, back in the old times; data, in its stored state, seemed to want to be vibrated, or at least to be near a vibration, each with their own frequency, their own rhythm. There were the rotating disks of old hard drives and CD-Rs, the whirring cooling fans that were necessary once these were replaced with solid state drives, and the building's HVAC fans that drove conditioned air through sealed vents. I waved away some of the dry ice vapor from my knees and from Anita's face, which had become almost fully enveloped. "Bah!" she giggled.

Ally's panning briefly passed over a member of the film crew, a guy with long, stringy hair, wearing an expression that suggested he didn't want to be alone with his thoughts. The silence always seemed to eat away at him. I wished, sometimes, that I had a scientific reason to look at the old pictures of me, the thousands of them my parents had taken over the first few years of my life, sent in a daily stream to their parents, my grandparents. I can still hear that digital camera click in my dreams, like a sword being sharpened.

I'd heard that parents back then documented every moment of their babies' lives, keeping permanent records of their meals, their naps, their bowel movements. It was for optimization, so they could detect patterns and learn what their babies secretly wanted, secretly needed. To speak with them across that gap in language. But to me, it felt like a deliberate copying, like parents were making a clone of their child out of data in case the real thing disappeared, as every parent was afraid their babies would: stolen by a stranger, or destroyed by calamity, or condemned to some apocalypse.

Our parents disappeared instead.

What happened, in the de-referencing—and I should not be telling you this; do not tell anyone that I am telling you this—was due to an excess of information. People had generated so much data about themselves online (comments, clicks, searches, and so forth) that corporations like the Six Companies had created virtual versions of their users. They used these virtual people as test cases, to experiment on what products their users would like to see ads for, or who they might want to be friends with. And then, one day, the buffer overflowed; the references got scrambled. User number 13155 was my mother, and all her data pointed to this identifier; now all her data pointed to some other number, unknown to her, and user number 13155 pointed to someone else's data entirely, totally altering what she saw online. (I know it seems strange that people would take something on a computer to be real, but it was, it really was.) At first, it was just the different ads she got that were disorienting—"Proud to be a financial professional" hats, or discount ammunition. Then it was the entirely different network of friends and family she saw in her feed, wishing her happy birthday three months too early. Her financial history, too: the things she owned, the money she owed; all different, now. She was the proud owner of a sailboat and $424,000 in debt. It takes a strong personality not to be affected by a barrage of casual signals that you aren't who you think you are.

And there was no way to restore things to the way they had been. We could have declared data bankruptcy, erased it all and started again. Free from obligations, free from debts; unburdened, but unbuilt. But the companies didn't want to do that, and, surprisingly, a lot of the people didn't, either. They didn't want to let go of their past selves, of the possibility that they might return to the identity they'd lost. And so, without really making a conscious decision to do so, everyone had tried their hardest to adopt the new identities they'd been randomly assigned. My mom—a lifelong frugal Democrat and photographer—attempted to become a gun- and boat-owning, financially profligate, Virgo accountant. She tried her best. I want you to know that. She really did.

But identity isn't a random assignment. It's dependent on the realities of your body, of your world; the shape of your face, your resting expression, the tendencies of your mind, where you live, what you can eat. Your parents. Your children. The people you love and who love you. You can't take one identity off and put another one on without consequences. Mom was an artist; she would always, in some way, be an artist, and it was crippling to act like she wasn't. The transplants didn't take; the new identities were rejected by their hosts, and mom—and everyone like her—was left with nothing. By the time it was clear what was happening, no one could stop it. The de-referenced became blank, disidentified. For those adults unaffected by the de-referencing, all they could do was wait for the storm to pass. They've been cleaning up the mess ever since.

"There," Sutwin said. "It's coming from the cafeteria on the 47th floor, maybe 50 feet west of the room."

We went through the confirmation process. Anita curled up on a pillow we'd placed in the corner, sucking her fingers with relish.

”Extracting next sound," Ally said. "Transform expected to take 27 minutes."

I thought about my isolation from everyone else in the room, about being my own conscience. I was happy standing alone, but I was decidedly different from the typical data orphan, many of whom have built their identity around their new family. After their parents disappeared, most were raised together in big group houses or loft spaces by local adults who hadn't been de-referenced, a patchwork of digitally illiterate seniors and paranoid conspiracists who took up the parenting slack in an ad-hoc fashion. Most data orphans still lived in these communal spaces, and talked about their fellow orphans as their true families. (That this identity excluded those they'd kicked out of the group homes for some infraction, or who had fled due to abuse, went unaddressed.) Their reference for who they were, for how to act, for how to be, was each other. But then, what else did they have? They had to create new references. The old ones were gone.

I, however, had been raised, alone, by my kind-but-distant Uncle Ypsli, who had lost his wife and adult children to the cataclysm. Uncle Ypsli was most animated when he'd talk about my dad, his brother; how this man had only wanted to show people that he world contained so many opportunities for beauty—you just had to work together with strangers to bring that beauty about; that this had been the point, ultimately, of his most famous work, of "Fundamental Frequency." And, too, how much my father had changed when he de-referenced, when all the information about him and his life and his work was switched with some racist elementary school principal. How, for a time, he'd become hard, bitter. And then he'd become nothing at all. Because of this remaining thread connecting me to my old family, it had taken me a while to accept that I wasn't my father's child—your child—anymore. That I couldn't define myself in reference to you.

I'd found some contraband self-help books for actual orphans, published before the cataclysm, but they didn't quite apply to what I was facing. My parents weren't gone, after all. They'd just changed, forgotten me. Like the de-referenced who refused to accept that their old data was gone and they needed to start anew, I struggled for years to accept that my parents couldn't come back to me, even though they were right there—right here. But I did find a way, in the end, to accept that I was unconnected to anyone. And I liked it that way, I thought. I certainly wouldn't be having children. Though I did enjoy being around Anita, our quiet little nuclear reactor, churning on in isolated determination as we adults went about our separate tasks.

As the extraction process went forward—we could legally only isolate one sound at a time, and had to discard anything we'd confirmed—Ally let the full length of the room tone play, all 60 seconds' worth, in a loop. It was so familiar to us that I hardly even noticed it anymore; sometimes, in the shower, I found myself singing it, MmMmMmMmfsssssssss…pmp, pmp, pmp. Anita got up from her pillow and stopped in front of me, where a dense pocket of vapor had collected. She twirled, holding her arms out at her sides, cutting through the fog, and swirling it outward in widening eddies. She rotated; she vibrated, like we all do, we masses of atoms; we collections of sympathetic waves.

Then Anita fell, and after a moment of wide-eyed indignation, pouted her bottom lip and squeezed her cheeks up and yelled, open-mouthed, singing a little melody about pain. Vashti took three quick steps across the room and scooped her daughter up, one hand on her behind and the other rubbing her back. Instantly, Anita's mood changed; after a few cycles of rubbings, she pushed herself away from Vashti's body, put both hands on her cheeks and said, declaratively, "My mama." Vashti responded, echoing, "My Annie"; Anita giggled and replied with "Mama," and they volleyed and forth a few times—"Annie," "Mama," "Annie," "Mama"—until Anita was radiant once more. Soothed, the little girl pressed her ear to her mother's chest, and Vashti began humming, in a low voice, "Annnnieee…Annnnnnnnnnieeeee…" The consonant in the middle of her nickname rang deep in Vashti's chest, like a bell. Anita closed her eyes and hummed back a tone of her own, but it didn't quite match, and the two pitches beat against one another, wobbling in the surrounding air—wub,wub-wub-wuuuub-wuuuuuuuub—.

Suddenly, despite the noise in the room, I heard something in the recording. It wasn't right there in the foreground. But behind the hum of fans and elevators and plumbing, I heard a terrifyingly familiar sound. I made a noise, or must have made a noise, some sort of cry; everyone turned to look at me.

"Sheila?" Vashti said. "Do you hear something?"

Anita, struggling out of her mother’s embrace, walked over and put her hand on my knee, a look of concern on her face. The sound certainly was familiar to me; it sounded like a laser beam. "Fundamental Frequency," my dad's resonant artwork. Your artwork. (Let me say it into your ear now, let me confirm it: you are my dad.) How did it get there? I recalled that the Six Companies, after the cataclysm began, had given money away almost indiscriminately in a bid to generate good publicity. That's why the student film had been using the corporate offices as a set: an in-kind donation. The company must have reached out to you, too, offered you a commission.

Maybe, I thought, when you brought the piece into the company’s HQ, into enemy territory, you amped up its power. Set it to the exact resonant frequency of the concrete slab. Put in bigger speakers. Installed it right by the roof. Made it capable of disrupting the baffler. Turned it on and let it run. Programmed it to kick into a high volume maybe a few weeks after you left it there, to cover your tracks. When it amped up, expanding infinitely outward in a feedback loop, it froze the baffler in place. Then the winds took the building. Onlookers in the parking lot reported the sound of plastic clamshell packaging being crumpled, or of trumpets. You might've been satisfied with what you accomplished. Or, by that time, you might have already forgotten.

I know why you did it, dad. Mom was gone, and you could feel yourself slipping away, too. Maybe you didn't even know what you were doing. Maybe the data of that racist principal was driving you to this violence, this evil act of which I don't think you would have been capable, before; at least, not as Uncle Ypsli portrayed you. But, as I sit here, saying this into your ear, both of those people—old-you and new-you—are gone. It's all been cleaned now. I want to show you the video of your piece, but we're not allowed. They worry that if we let your old self slip in, the corrupted self might, too, through some latent association we can't really understand. But this I understand: "Fundamental Frequency," why you made it in the first place, and why you put it to such grim use. If beauty has power, then it has the power to destroy. That's why I'm telling you all this. To give you at least this small point against which you can orient yourself. Something to build an identity on.

"Sheila?" Vashti said, prompting me again.

"I thought I heard a new resonance," I said, hesitantly. "A sword, maybe, or a bright beam. Something open, singing. Or vibrating on a pedestal. But it disappeared."

"Are you sure?" Vasht said. "Maybe it was there all along. We can go back and isolate it."

"No," I said. "It must've been some accidental confluence with the conditions in the room. Some momentary alignment."

"Let me rewind," said Ally, not giving up. "See if you can hear it again." The tape squelched backward.

Before I learned the science of sound, I thought that the waves must go on forever. That they emerged from a person's mouth and then just kept going, into their child's ears and into the air and then into space, onward and outward. I thought that, if I traveled to a point just past Mercury, I could hear the last words you said to me before you lost yourself, the last sweet nothings cooed in my ear as I drifted off to sleep. But sound needs a medium, and can't exist beyond the atmosphere; on Earth, its energy is absorbed: by the walls, by the atmosphere, by the body. And there's no way to get it back. It's moved on, converted into something new. You and mom made me and then you dissolved, forever.

I was, at the time, considering quitting this research because it felt, honestly, like being trapped in a whirlpool, circling in ever-tighter spirals toward some point in the past we couldn't escape, no matter what we discovered. The tower was alway collapsing. I was always losing you. But this is what we chose; we exist now in an eternal moment. After the great de-referencing, the ones who survived—or, I should say, the ones who kept themselves—put a halt to progress. We no longer built up and out; we cycled, from one day to the next, from one season to the next, repeating our patterns. Vibrating, albeit slowly. Without references to what happened in the past, to what we've accumulated or accomplished, we are, by necessity, unbuilt. There's no solid ground. The old references disappeared, and we're not allowed to make new ones. But we make them anyway—unofficially, impermanently. The data orphans and their insular communities, we researchers in this room, Anita and Vashti, bound by blood. Which is really just to say: parents and children spend so much time together that they can never truly be apart. They exist in relation to one another, harmoniously or in opposition.

That's why, after I told the team all of this, I came to get you. It didn't matter who you thought you were. You would always be mine.

Back in the room, they were waiting for my answer.

"All right," I sighed, resigned but excited. "Let's give it one more try."